Entertainment

How I became a translator (Translating India-9)

(ATTN EDITORS: This is the ninth in a 10-part “Translating India” series where noted translators — in articles written exclusively for IANS — share their experiences of translating from their respective languages.)

By Keerti Ramachandra

Did I always want to be a translator? No. I became a translator by default. When asked if I could translate Jayant Kaikini’s short story “Amrithaballi Kashaya”, I said, of course!

I know Kannada, my command over English is good, I can easily do it. So, what if I had never translated anything before!

Shock number one — reading Kannada is very different from speaking Kannada. Some words and phrases Kaikini had used were alien to me since I was familiar with Dharwar Kannada. But I knew Mumbai, and the kind of life people led in its chawls and suburbs. So, armed with Rev. Kittel’s Kannada-to-English dictionary, I set off on a journey with Gangadhar and Mayee, Vicki and Bandya and The Golden Frame Works.

Soon I was deeply involved in their lives, they haunted me until I finished my work. The editor stepped in, made changes, leaving me fretting, fuming, ranting. How can she do this? She doesn’t know Kannada, that’s not how the author says it… I protested. Today I know better. Editing is very much a part of the process of translation.

In 1996, I was commissioned by Vishwas Patil to translate his Sahitya Akademi award-winning novel “Jhadajhadati” into English on a common friend’s recommendation. He knew nothing about me, except that I spoke Marathi well, but that I had never studied Marathi, nor did I have even a nodding acquaintance with Marathi (or for that matter Kannada) literature! I knew nothing about him either. (So much for those who say one must be familiar with everything about the author and his work!)

Agreeing to translate “Jhadajhadati” (“A Dirge for the Dammed”) seemed like an act of utter foolhardiness. While I knew the customs, rituals, superstitions and beliefs of the people, I was half Maharashtrian after all, everything else was unfamiliar. The setting was rural, much of the dialogue in a dialect, the topography I could not visualise. Serious research was required before I actually started translating. Long telephonic conversations with the author helped. And a fortuitous visit to a farm in rural Maharashtra halfway through the work lent a little more credibility to my effort.

“Jhadajhadati” is a novel I haven’t been able to get out of my system. It had integrity, sincerity, empathy, even sentimentality. It was a harsh, cruel reality Patil had portrayed. I knew then that I would always be a heart driven translator. The editor in me would later prune, refine and ground it. The challenges the novel presented were innumerable, but all translators encounter them. But unique to this work was the dialect, a “legitimate” variety of Marathi. There were folk songs and very local idioms and proverbs.

Sometimes the original laboured a point, the emotions were excessive, the situations clichéd. All of those were perfectly acceptable in Marathi, but in English they sounded repetitive, exaggerated and excessive. Deciding what to abridge, what to modify, when to take liberties and when to be faithful, was tough. In my attempt to be accurate I chose to retain many Marathi words, which some critics objected to. Some literal translations of idiomatic expressions and proverbs were appreciated. As one reviewer said, such literal translations “enrich the target language”. He was not Indian!

After this novel about displacement and rehabilitation, came Patil’s fictionalised biography of Subhas Chandra Bose, with its own set of demands. The primary research was in English, the novel was in Marathi and now translated into English. How did one make the Japanese and the Germans not sound like Indians speaking English? In the original, they all spoke the same brand of Marathi!

As a translator, I set great store by dialogue because I feel how a character speaks indicates much more than the mere words she/he utters. Using casual terms of address, the plural for “we” for oneself, the pronunciation of certain words, all indicate the background, the attitude, the relationship of the speaker with the others.

To hear these variations, I need a good “ear”, especially because I translate from more than one language. The cadences, rhythm, lilt and melody of Marathi Gadgil differs from that of Kannada Bolwar and Hindi/Urdu Joginder Paul. Also, does Mr Gadgil’s voice differ from Mrs Vijaya Rajadhyaksha’s? How do I, using the one standard English, ensure that all these writers do not sound like Keerti Ramachandra speaking in English?

I often wonder what my relationship with the author and with the text is. Am I intimidated by the author? Yes. Translation is therefore a huge responsibility to ensure no damage is done to the author’s reputation. Am I daunted by the text? Sometimes. Is that why I tend to anchor the translation in the original? Can I set it free without making it my own? Should I?

After 25 years as a translator I find myself asking more questions than I did before. I read something I liked and immediately put pen to paper. Ah, those days of innocence. But I will continue to translate, to ask questions and hope those who have found the answers will share them with me.

(Keerti Ramachandra has many years of editing, writing, teaching and translating. She can be contacted at [email protected])

–IANS

Keerti/ss/sac

Entertainment

Casino Days Reveal Internal Data on Most Popular Smartphones

International online casino Casino Days has published a report sharing their internal data on what types and brands of devices are used to play on the platform by users from the South Asian region.

Such aggregate data analyses allow the operator to optimise their website for the brands and models of devices people are actually using.

The insights gained through the research also help Casino Days tailor their services based on the better understanding of their clients and their needs.

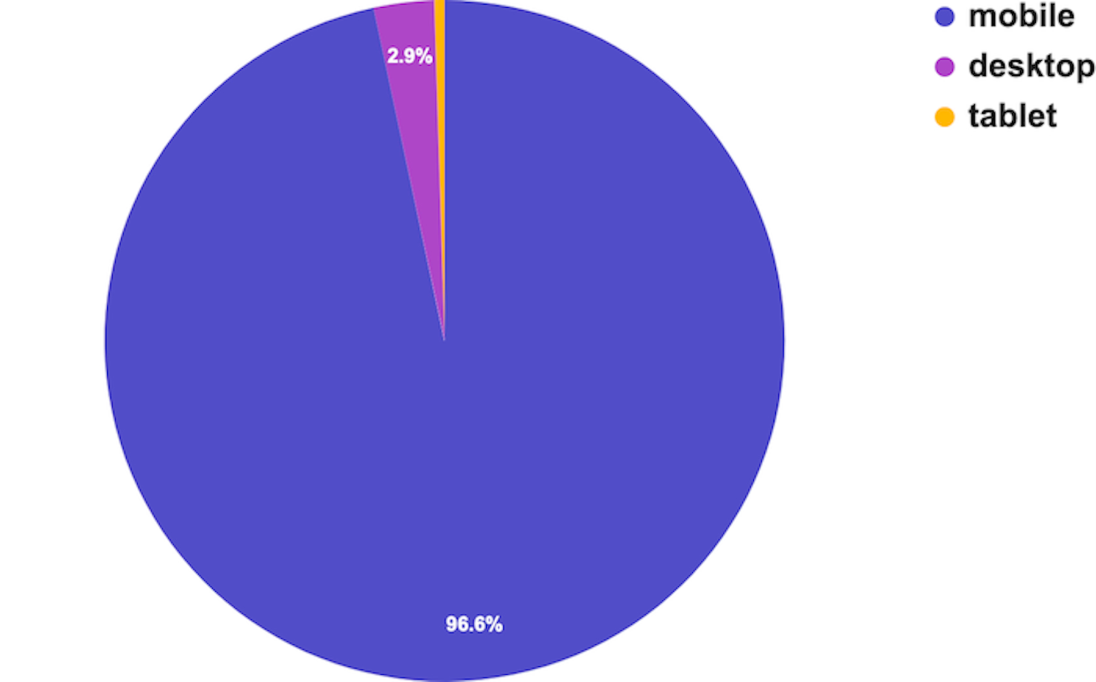

Desktops and Tablets Lose the Battle vs Mobile

The primary data samples analysed by Casino Days reveal that mobile connections dominate the market in South Asia and are responsible for a whopping 96.6% of gaming sessions, while computers and tablets have negligible shares of 2.9% and 0.5% respectively.

The authors of the study point out that historically, playing online casino was exclusively done on computers, and attribute thе major shift to mobile that has unfolded over time to the wide spread of cheaper smartphones and mobile data plans in South Asia.

“Some of the reasons behind this massive difference in device type are affordability, technical advantages, as well as cheaper and more obtainable internet plans for mobiles than those for computers,” the researchers comment.

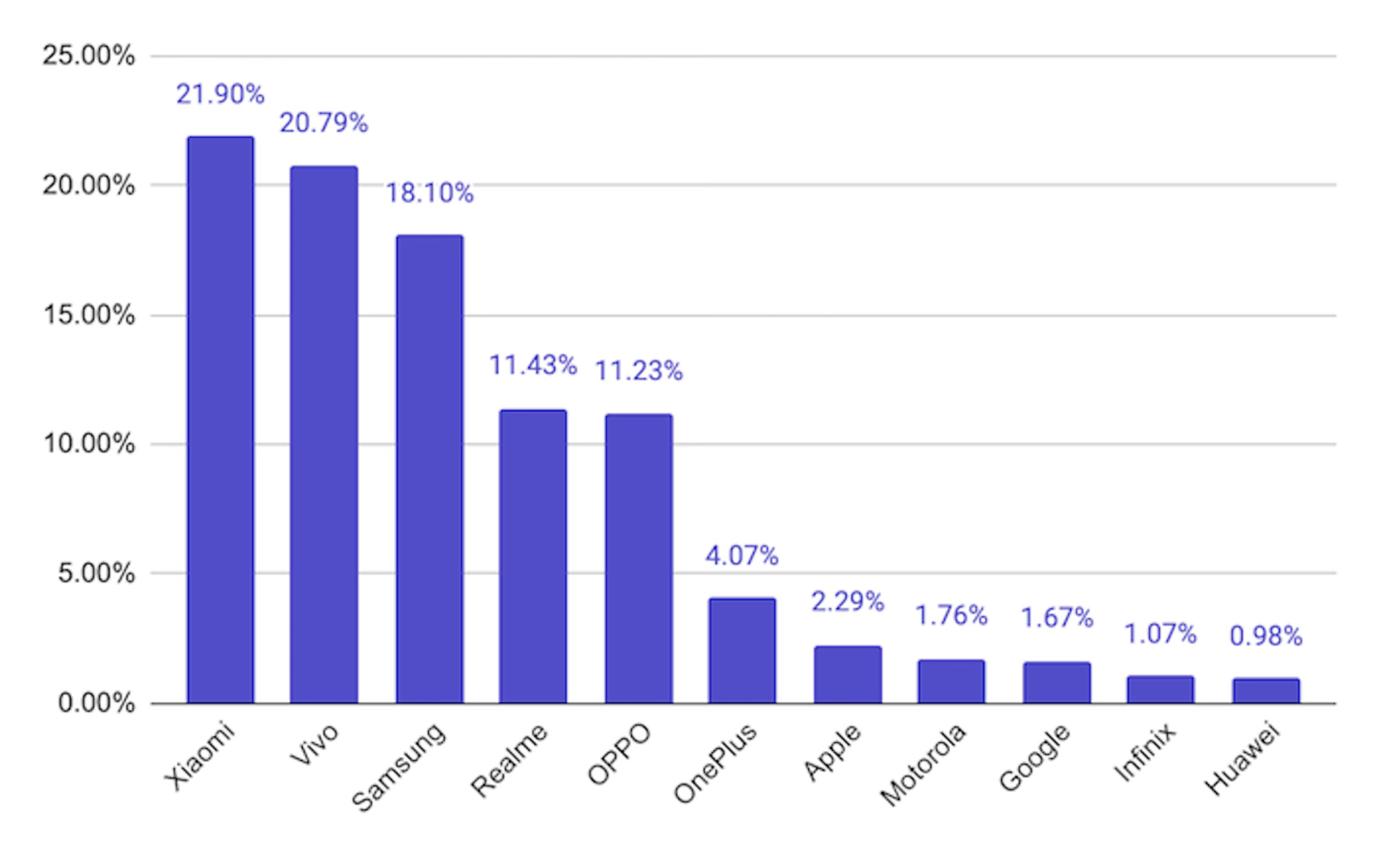

Xiaomi and Vivo Outperform Samsung, Apple Way Down in Rankings

Chinese brands Xiaomi and Vivo were used by 21.9% and 20.79% of Casino Days players from South Asia respectively, and together with the positioned in third place with a 18.1% share South Korean brand Samsung dominate the market among real money gamers in the region.

Cupertino, California-based Apple is way down in seventh with a user share of just 2.29%, overshadowed by Chinese brands Realme (11.43%), OPPO (11.23%), and OnePlus (4.07%).

Huawei is at the very bottom of the chart with a tiny share just below the single percent mark, trailing behind mobile devices by Motorola, Google, and Infinix.

The data on actual phone usage provided by Casino Days, even though limited to the gaming parts of the population of South Asia, paints a different picture from global statistics on smartphone shipments by vendors.

Apple and Samsung have been sharing the worldwide lead for over a decade, while current regional leader Xiaomi secured their third position globally just a couple of years ago.

Striking Android Dominance among South Asian Real Money Gaming Communities

The shifted market share patterns of the world’s top smartphone brands in South Asia observed by the Casino Days research paper reveal a striking dominance of Android devices at the expense of iOS-powered phones.

On the global level, Android enjoys a comfortable lead with a sizable 68.79% share which grows to nearly 79% when we look at the whole continent of Asia. The data on South Asian real money gaming communities suggests that Android’s dominance grows even higher and is north of the 90% mark.

Among the major factors behind these figures, the authors of the study point to the relative affordability of and greater availability of Android devices in the region, especially when manufactured locally in countries like India and Vietnam.

“And, with influencers and tech reviews putting emphasis on Android devices, the choice of mobile phone brand and OS becomes easy; Android has a much wider range of products and caters to the Asian online casino market in ways that Apple can’t due to technical limitations,” the researchers add.

The far better integration achieved by Google Pay compared to its counterpart Apple Pay has also played a crucial role in shaping the existing smartphone market trends.

Content provided by Adverloom